1 Policy summary

It is a general, legal and ethical principle that valid consent must be obtained before providing care and, or treatment (including examination) to a patient. This principle reflects the right of patients to determine what happens to their own bodies and is a fundamental part of good practice.

2 Introduction

Care and, or treatment can only be provided to someone with their valid consent or with specific legal authority (which may be provided through the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA), Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), Children Act, Court of protection, Common Law etc.). However, the only circumstances in which a patient may be treated without consent for their mental disorder is those patients detained or liable to be detained under the MHA. Refer to part 4 of the MHA and Chapter 23 of the Code of Practice (MHA 2015).

Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014: Regulation 11 “Need for Consent”.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) include consent as part of their ongoing monitoring process as part of the “key lines of enquiry”. Regulation 11 sections 11(1) to 11(5).

As a care provider Rotherham, Doncaster and South Humber NHS Foundation Trust (RDaSH) (the trust) must make sure that consent is obtained lawfully and that the person who obtains the consent has the necessary knowledge and understanding of the care and, or treatment that they are asking consent for.

3 Purpose

The purpose of this policy is to set out the standards and procedures within the trust to enable staff to be compliant with the requirements or guidance on consent. While this document is primarily concerned with healthcare, social care colleagues should also be aware of their obligations to obtain consent before providing certain forms of social care interventions, such as those that involve touching the patient. This policy also incorporates guidance that is relevant to patients detained under the MHA where consent is required.

4 Scope

This policy applies to all staff employed by Rotherham, Doncaster and South Humber NHS Foundation Trust (RDaSH), permanent or temporary who are involved in providing care and treatment.

For further information about responsibilities, accountabilities and duties of all employees, please see appendix A.

5 Procedure

5.1 Quick guide

5.1.1.1 Consent

It is a general, legal and ethical principle that valid consent must be obtained before providing care and, or treatment (including examination) to a patient. This principle reflects the right of patients to determine what happens to their own bodies and is a fundamental part of good practice.

5.1.1.2 Verbal consent

It will not usually be necessary to gain separate written consent to routine and low-risk procedures, such as providing personal care, general health checks, taking a blood sample for routine tests or medication which is considered low risk to the patient.

5.1.1.3 High risk or risk of serious harm

For interventions, care and, or treatment that present a high risk of mortality or risk of serious harm (adults or young people 16 and over), staff should seek written consent. This includes medication which needs close monitoring or has significant side effects such as:

- antipsychotics (oral and any intramuscular (IM)) such as clozapine which has a strict monitoring regime involving the requirement for regular blood tests to be taken

- Lithium which requires monitoring on blood levels, checks for thyroid and renal functioning, Serum calcium levels and blood pressure

- soft tissue podiatry surgery such as procedures involving the use of anaesthetic

5.1.1.4 Refused consent

If an adult (16 and over) with capacity makes a voluntary and appropriately informed decision to refuse care or treatment, this decision must be respected, except in certain circumstances as defined in the MHA 1983 or in exceptional circumstances under common law.

5.1.1.5 Lack of capacity

A patient aged 16 and over who lacks capacity can, following a capacity assessment be given treatment if it is in their best interests in accordance with the MCA, providing the treatment has not been refused by a valid and applicable advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) or consent is refused by an attorney for health and welfare under a lasting power of attorney (LPA) or by a court appointed deputy for health and welfare.

5.1.1.6 When should consent be sought?

Consent should be sought from all patients before they are provided with care and, or treatment.

5.1.2 Routine care and treatment

It will not usually be necessary to gain separate written consent to routine and low-risk procedures, such as providing personal care, general health checks, taking a blood sample for routine tests or medication which is considered low risk to the patient.

In many cases, it will be appropriate for a health professional to provide the care and, or treatment immediately after discussing it with the patient. If the patient is willing for the care and, or treatment to be given, they will then give their consent and the care and, or treatment can be given immediately. In many such cases, consent will be given verbally.

In some cases, patients may consent by complying with the proposed care or treatment, for example rolling up their sleeve to have their blood pressure taken. However implied consent is not sufficient to demonstrate an understanding about the proposed intervention.

Even though consent in writing is not required from the patient, healthcare professionals should refer to the person’s ability to give consent or show an understanding of the proposed intervention in the patient’s health record as part of their care plan. Or where the person lacks capacity to consent, show that they are providing the care and, or treatment under the MCA in the person’s best interests or under the provisions of the MHA.

However, if any member of staff has any reason to believe that the consent may be disputed later or if the procedure is of particular concern to the patient (for example if they have declined or became very distressed about similar care in the past); it is advisable to complete a written consent form 1.

5.1.3 Treatment that may present high risk or risk of serious harm (adults or young people 16 or over)

For interventions, care and, or treatment that present a high risk of mortality or risk of serious harm, staff should seek written consent. This includes:

- medication which needs close monitoring or has significant side effects such as antipsychotics (oral and any intramuscular (IM)) such as clozapine which has a strict monitoring regime involving the requirement for regular blood tests to be taken. Lithium which requires monitoring on blood levels, checks for thyroid and renal functioning, Serum calcium levels and blood pressure

- soft tissue podiatry surgery such as procedures involving the use of anaesthetic

Where possible, discussion about the proposed care and, or treatment should be started well in advance of it being provided, allowing sufficient time for the patient to be provided with the relevant information about the care and, or treatment and the risks and benefits, to allow them time to ask questions and for staff to be able to respond to the patient’s questions. It must be explained to the patient that written consent is required.

If the patient can give valid consent, consent form 1 must be completed and signed by the health professional seeking consent and with an appropriate interpreter or advocate used if required. The patient should also sign and date the form.

If the patient is able to give consent but is physically unable to sign or unable to read or write, they may be able to make their mark on the consent form 1 to indicate consent. The mark should be witnessed by a person other than the member of staff seeking consent. The fact the patient has chosen to make their mark in this way should be recorded in the patient’s electronic health records.

Where there is any doubt about a patient’s capacity to give valid consent, capacity must be established before the patient is asked to give consent. Details of the assessment of capacity and conclusions reached must be recorded appropriately in the person’s electronic health records on MCA1 questionnaire.

For further guidance on obtaining valid consent see appendix C.

5.1.4 Children under the age of 16 years

Children under 16 may be able to consent to care or and or treatment if they have been assessed as Gillick competent to do so. The assessment of competence in under 16’s should be appropriate to the child’s age.

Staff should record the assessment on the Gillick competence template available on the electronic patient record.

For interventions, care and, or treatment that present a high risk of mortality or risk of serious harm, staff should seek written consent once Gillick competence has been established.

Even if a child under 16 is Gillick competent to give their own consent to a particular treatment, it is still good practice to involve someone with parental responsibility in the decision-making process, unless the child specifically asks for the information to be kept confidential and cannot be persuaded otherwise. Their confidentiality should be respected unless non-disclosure of the information may expose the child to a risk of serious harm.

Where a child is Gillick competent to give consent to the care and or treatment, consent form 1 should be used. There is space on the form for a parent to countersign if a competent child wishes them to do so.

For further guidance on obtaining valid consent from patients aged 16 or under see appendix D.

5.1.5 Research and innovative treatment

The same legal principles apply when seeking consent for research purposes as when seeking consent for other care or treatment. If treatment being offered is of an experimental nature, clear explanations, and evidence to date of the effectiveness of that treatment, plus how it differs from the usual methods and a clear explanation about any additional risks or uncertainties must be provided by the healthcare professional.

No blood sample taken in the trust is used for research purposes unless the patient has opted in with written informed consent for their sample to be kept and used.

5.2 Who should seek consent?

All staff providing care and, or treatment are responsible for checking that the patient has given valid consent before the care or treatment begins.

Staff must have sufficient knowledge of the proposed care and, or treatment and understand the risks involved to be able to provide any information the patient may require. Inappropriate delegation could result in the consent obtained being invalid.

It is the healthcare professional’s own responsibility that when they require or request a colleague to seek valid consent on their behalf they are confident that the colleague is competent to do so.

Where an anaesthetist is involved in a patient’s care, for example, in administering electro convulsive treatment (ECT), it is their responsibility to seek valid consent for anaesthesia, having discussed the benefits and risks. See the electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) clinical guidelines policy.

If a member of staff feels pressurised to seek consent or they have any concerns about lack of understanding of the process, they must not proceed in seeking the patient’s consent and must speak to their manager. The executive medical director may also be contacted for advice.

5.3 Duration of consent

When a patient gives valid consent, that consent is valid for an indefinite duration unless it is withdrawn by the patient. Consent should be reconsidered when:

- there has been a delay in the treatment being provided

- new information comes to light about a treatment or if the risks or benefits of the treatment change

- concerns are raised about the patient’s capacity to consent

- where the treatment and, or monitoring for that treatment is ongoing, consent should be revisited at specified intervals

5.4 Withdrawal of consent, patients aged 16 years or older

Patients (not currently managed under a treatment section of the MHA) should be told that their consent to treatment can be withdrawn at any time. Where patients withdraw their consent or are considering withdrawing it, they should be given a clear explanation of the likely consequences of not receiving the treatment. A person with capacity is entitled to withdraw consent at any time.

If the patient has already signed a consent form 1 but then changes their mind, the patient should sign and date another consent form 1 again to confirm their wishes.

The health professional, should record the reason consent has been withdrawn, sign and date the new consent form 1.

If there are any concerns about the patient’s capacity to understand the consequences of withdrawing consent, an assessment of capacity should be undertaken. Details of the assessment of capacity and conclusions reached must be recorded in the person’s electronic health records, in keeping with the trust’s Mental Capacity Act (MCA) (2005) policy.

Where the person lacks capacity to withdraw consent, a decision will need to be taken under the MHA or MCA best interests whether to not proceed with the care and, or treatment.

5.5 When consent is refused, patients aged 16 years or older

If the process of seeking consent is to be a meaningful one, refusal must be one of the patient’s options.

If a patient (16 and over) with capacity makes a voluntary and appropriately informed decision to refuse care or treatment, this decision must be respected, except in certain circumstances as defined in the MHA 1983 or in exceptional circumstances under common law.

If, after discussion of possible care or treatment options, a patient with capacity refuses any care and, or treatment, this fact should be clearly documented on the patient’s record.

If the refusal of the care or treatment presents risk of serious harm to the patient, staff should complete an informed refusal form (consent form 3) to evidence that they have discussed the person’s condition with them and explained the proposed care and, or treatment with the patient or in the case of equipment for example the related risks of declining its use.

The form should be signed and dated by the patient and witness or staff member who has undertaken the discussion and held on the patient’s electronic record.

5.6 Patients aged 16 years or older who lack capacity to consent

In most cases, parents, relatives, or members of the healthcare team cannot consent on behalf of a patient aged 16 and over.

A patient aged 16 and over who lacks capacity can, following a capacity assessment be given treatment if it is in their best interests in accordance with the MCA, providing the treatment has not been refused by a valid and applicable advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) or consent is refused by an attorney for health and welfare under a lasting power of attorney (LPA) or by a court appointed deputy for health and welfare.

Where a patient has been assessed as lacking capacity to give consent to interventions, care and, or treatment that presents high risk or risk of serious harm, the assessment must be appropriately documented. Consent form 4 should be used to evidence the outcome of the assessment of capacity.

Consent form 4 should also provide details of the Best Interest decision taken by the health professional proposing the treatment in the patient’s best interests.

Details whether there is a valid and applicable ADRT, LPA or a court appointed deputy authorised to make the decision should also be recorded on the consent form 4 and where applicable signed by the appointed person.

Consent form 4 should be signed and dated by the health professional seeking consent and where appropriate by anyone giving a second opinion.

5.6.1 Independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA)

Where a serious medical intervention is proposed or where there would be serious consequences if the treatment was not provided for a patient who lacks capacity and there are no family or friends who can be consulted as part of the best interested process other than paid carers, then the trust has a duty to instruct an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA). The IMCAwill help establish the best interests of the patient but is not the decision maker. In an emergency where there is no time to refer to an IMCA then the healthcare professional can and should act in the patient’s best interest but should review as soon as an IMCA is available.

5.7 Children or young people who are not Gillick competent, parental responsibility

If a child or young person under 16 is not Gillick competent to give consent, then consent should be sought from a person with parental responsibility providing the decision is within the scope of the parental responsibility. People with parental responsibility for a child include:

- the child or young person’s birth mother

- the child or young person’s father if married to the mother at the child or young person’s conception, birth or later

- civil partners and partners of mothers registered as the child or young person’s legal parent on the birth certificate

- the local authority if the child or young person is subject to a care order or a person named in a residence order or parental responsibility order in respect of the child or young person

Fathers who have never been married to the child or young person’s mother will only have parental responsibility if their name appears on the birth certificate (for births since 1 December 2003) or if they have acquired parental responsibility through a court order or parental responsibility agreement. Legally, consent is only needed from one person with parental responsibility, although it is good practice to involve all those close to the child or young person in the decision-making process where appropriate.

Consent form 2 should be used to document consent to a child or young person’s treatment, where that consent is being given by a person with parental responsibility for the child or young person.

For complex serious medical treatment decisions legal advice may be needed to clarify if the decision is within the scope of parental responsibility.

5.8 Refusal of treatment children and young people

Where a young person aged 16 or 17 who could consent to treatment in accordance with the MCA, or a child under 16 who is Gillick competent refuses treatment, it is possible that such a refusal could be overruled by someone with parental responsibility.

In these cases, or if a person with parental responsibility for a child under 16 who is not Gillick competent refuses treatment, there should be evidence that the risks have been considered and explored.

If the refusal of the care or treatment may cause significant harm to the patient, staff should complete an informed refusal form (consent form 3) to evidence that they have discussed the patient’s condition with them and where applicable the person with parental responsibility and explained the proposed care and, or treatment. It should also evidence that the person and where applicable the person with parental responsibility has been informed of advantages of receiving the treatment and the risks associated with non-concordance.

- The form should be signed and dated by the patient or person with parental responsibility and witnessed by the staff member who has undertaken the discussion and held on the patient’s electronic record.

- The patient’s health records should document fully what decisions were made and why, including whether the use of the MHA to treat the patient would have been appropriate or not.

- Consideration should be made in respect of a referral to children’s social care. Contact the safeguarding team for advice and support.

Where there are disagreements about whether a child or young person should be treated, staff should seek legal advice and if necessary, a decision from the court, especially if faced with a competent under 18-year-old who is refusing consent to treatment, in order to determine whether it is lawful to treat them in the face of their refusal.

5.9 End of life care

For some people who are entering the last days of life, mental capacity to understand and engage in shared decision-making and the ability to consent to treatment may be limited. This could be temporary or fluctuating, for example it may be caused by delirium associated with an infection or a biochemical imbalance such as dehydration or organ failure, or it could be a permanent loss of capacity from dementia or other similar irreversible conditions. However, the framework for seeking consent towards the end of a patient’s life is essentially the same as for any care and treatment.

5.9.1 Advance consent

If a patient has a condition that will impair their capacity as it progresses or is otherwise facing a situation in which loss or impairment of capacity is a foreseeable possibility, the healthcare professionals responsible for their care should encourage them to think about what they might want for themselves should this happen, and to discuss their wishes and concerns with the healthcare team as soon as possible whilst they have capacity to do so. In order to give advance consent, the patient must clearly articulate the particular care and, or treatments to which they are consenting to in an advance statement. However, the advance statement is not legally binding but should be taken into account when the person lacks capacity, and it is being decided what is in their best interests. If the patient does not want to receive a particular treatment, they should be encouraged to write an advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) which can be used at the time they may lack capacity, in which case if valid and applicable they should not be provided with the treatment in line with their wishes.

5.10 When patients do not want to know

If a patient does not want to know in detail about their condition or the care or treatment, staff should respect their wishes as far as possible, but must explain the importance of providing at least the basic information they need in order to give valid consent to the care and, or treatment being given.

The patient must be informed that they can change their mind and have more information at any time. This needs to be recorded in the patient’s electronic record.

The health professional seeking consent must record the fact that the patient has declined relevant information to be able to give valid consent to the care or treatment.

The health professional will need to make a decision about proceeding with the treatment in this situation.

If the treatment involves significant risk the health professional should seek advice from the relevant clinical lead or associate medical director.

5.11 Consent to visual and audio recordings

Consent should be obtained for any visual or audio recording, including photographs or visual images relating to examination or treatment. The purpose and possible use of recordings must be clearly explained to the patient before their consent is sought for the recording to be made. If recordings are to be used for teaching, audit or research, patients must be aware that they can refuse to consent without their care being compromised. Recordings are to be anonymised prior to use.

5.12 Emergencies

In situations where a patient is conscious, where possible, consent still needs to be sought from patients for emergency treatment, if they have capacity to be able to give it.

If the emergency is so significant, for example, lifesaving, that there is no time to seek consent or the patient is unconscious (for example, IM Naloxone in opioid overdose or IM Glucagon in diabetic emergency) the rationale for the treatment must be recorded in the patient’s electronic health records. Once recovered the reasons why treatment was necessary should be fully explained to the patient.

However, if staff are aware that there is a valid and applicable advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) in place this should be respected, and the treatment should not be given. See the trust’s advance statements and advance decisions to refuse treatment policy.

5.13 Resuscitation status

Cardiac arrest by its nature means that a person will be unresponsive, not breathing and have no pulse. At this point they will therefore be unable to take on any information or give consent. It is vital that at the point of recognition of cardiac arrest (unresponsive and not breathing) that treatment, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is commenced immediately to give the optimum chance of survival.

Where a patient or clinical team has previously made decisions around refusal of CPR, this should be documented in a valid and applicable ADRT and, or valid form (for example, DNA CPR v13 or ReSPECT form).

Treatment in this case will be documented in the patient’s electronic health records and via the cardiac arrest report form.

5.14 Consent forms

Where written consent is required one of the following consent forms should be used:

- consent form 1, patients age 16 or over with capacity to consent to care and or treatment or children with Gillick competence to consent

- consent form 2, parent (or person who has parental responsibility) agreement to care and or treatment for a child or young person (under 16 years of age)

- consent form 3, informed refusal

- consent form 4, patients aged 16 or over who lack the capacity to consent to care and or treatment

Available on electronic patient records system or SystmOne. Completed consent forms must be scanned into the patient’s electronic record.

5.15 The Mental Health Act consent forms

The consent forms for patients detained or liable to be detained under the MHA differ from the Department of Health forms and can be obtained from each of the trust’s local Mental Health Act offices.

Regardless of which MHA consent form is used, the completed form(s) must be sent to the Mental Health Act office and a copy kept in the patient’s clinical electronic records.

5.16 Consent and the Mental Health Act (1983)

As a trust which provides mental health services and detains people under the Mental Health Act (1983) (MHA) it is important that the rules surrounding consent to treatment under the MHA are complied with. Consent to treatment under the MHA is an area which is subject to scrutiny by the CQC.

The sections contained in part 4 of the MHA are concerned with the treatment of patients suffering from mental disorder. All persons involved with this process should be familiar with the following:

- Mental Health Act Code of Practice (2015) (MHA)

- Code of Practice to the MHA 1983 (2015) (CoP)

- reference guide to the Mental Health Act 1983 (2015)

Under the MHA it is the responsible clinician (RC) who must ensure that the consent to treatment provisions are complied with. This policy should be read in conjunction with the MHA Code of Practice.

5.16.1 The Mental Health Act (1983) three, month rule

Consent to treatment (Part IV of the Mental Health Act (1983)) applies to patients that are detained under the Mental Health Act (1983) except those patients detained under:

- section 4

- section 5(2)

- section 5(4)

- section 35

- section 135

- section 136

- section 42 conditionally discharged patients

- section 58 of the MHA enables a course of medication to be imposed on a patient coming within the scope of this part of the act for up to 3 months without the patient’s consent and without the need to obtain an independent medical opinion. The protection provided by this section does not come into play until 3 months have elapsed since the commencement of the treatment

Authorisation for imposing the treatment on the patient during the initial 3 months is given by section 63.

During the 3 months, it remains good practice to try to gain the patient’s consent before any medication is administered.

5.17 Mental Health Act, consent to treatment forms

Patients detained under the MHA can receive treatment for their mental disorder (for example, medication) for up to three-months without their consent. Following the three-month period of detention, medicines for the treatment of mental disorder can only be given to the patient either with the patient’s valid consent or via a second opinion appointed doctor (SOAD).

For a patient who has given valid consent, the RC will record this on a Form T2 or CTO12.

For a patient who does not, or is unable, to give consent (for example, lacks capacity) a form T3 or CTO11 must be sought via a SOAD

(a CTO is a community treatment order)

5.18 Capacity and the Mental Health Act (1983)

Capacity should be re assessed “as appropriate” and a clear record made each time there is requirement to complete a form T2 in compliance with section 58 MHA.

5.19 Treatment and the Mental Health Act (1983)

Part 4 of the Mental Health Act (1983) (MHA) applies to all forms of medical treatment for mental disorder. However, certain types of treatment are subject to special rules set out in sections 57, 58, and 58A described below.

5.19.1 Section 57, treatment requiring consent and a second opinion

- This section applies to both detained and informal patients.

- It stipulates that no patient may be subject to psychosurgery or the implantation of female hormones into a man for the purpose of reducing sexual drive without the patients express consent and a second opinion.

- The second opinion is to be provided by a doctor appointed by the CQC. Treatments given under this section require careful consideration because of the ethical issues and possible long-term effects.

- Advice should be sought from the Mental Health Act office, as procedures for implementing this section must be agreed between the CQC and the trust.

5.19.2 Section 58, treatment requiring consent or a second opinion

- This section applies to all patients liable to be detained except for those detained under sections 4, 5(2) or 5(4), 35, 135, 136, 37(4),45A(5); conditionally discharged restricted patients, CTO patients not recalled to hospital.

- It covers the administration of medication for mental disorder (unless included in section 57 or 58A treatment) if three-months or more have lapsed since medication for mental disorder was first given to the patient during an unbroken period of detention (medication after three-months).

- If the above criteria apply, then the RC must personally seek the consent of the patient in order to continue with the proposed treatment.

- The patient must have the capacity to make the decision.

5.19.3 Section 58A, electro-convulsive therapy

This section applies to the following forms of medical treatment for mental disorder:

- electro-convulsive therapy

- such other forms of treatment as may be specified for the purposes of this section by regulations made by the appropriate national authority

This section applies to all patients aged 18 and above (whether they are detained) and all patients liable to be detained except for those detained under sections 4, 5(2) or 5(4), 35, 135, 136, 37(4),45A(5); conditionally discharged restricted patients, and CTO patients.

It covers electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) and treatments specified in the regulations (at the time of publication this is medication administered as part of ECT). Recorded on form 1B.

A detained patient aged 18 or over may only be given section 58A treatment if they have capacity (certified by an AC or SOAD) and have consented to it (for example, form T2), or, the patient does not have capacity, and it is appropriate treatment, and there is no refusal under the MCA, and this is certified by a SOAD (for example, form T3)

Patients aged under 18 may not be given section 58A treatment unless; the child is assessed as being competent and has consented to it, and, the treatment is appropriate, and is certified by a SOAD; or the child is assessed as not being competent, the treatment is appropriate, and, (patient 16 or 17 years old) there is no refusal under the MCA, and this is certified by a SOAD.

Further guidance regarding ECT and its legal provisions can be found in the Mental Health Act 1983 Code of Practice.

Does not apply to ECT if the ECT falls within section 62 or section 63 the first. Regulations about other section 58A treatments can say which of the categories of immediate necessity apply in each case.

5.19.4 Consent form for electro-convulsive treatment (ECT)

The consent form for ECT forms part of the ECT care record. This record is a complete document of all the required information for ECT, including consent. This has been through the ECT accreditation service (ECTAS) process. For further guidance staff should refer to the trust’s electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) clinical guidelines policy. The ECT Care Record can be accessed on the trust website via the electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) clinical guidelines policy.

Where an anaesthetist is involved in a patient’s care, for example, in administering electro convulsive treatment (ECT), it is their responsibility to seek valid consent for anaesthesia, having discussed the benefits and risks. Electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) clinical guidelines policy.

5.19.5 Part 4A, apply to community treatment order patients not recalled to hospital

Medical treatment for mental disorder may not be given (by anyone in any circumstances) to CTO patients who have not been recalled to hospital unless the requirements of part 4A are met

part 4A requires authority (for example, consent or MCA provision) and (if section 58 or section 58A type treatment) a SOAD certificate to confirm the treatment is appropriate

5.19.6 Section 63, treatments not requiring consent

Treatments that do not require the patient’s consent are all medical treatments for mental disorder given by or under the direction of the patient’s RC and which are not referred to in sections 57, 58 and 58A. This includes nursing, care, habilitation, and rehabilitation given under medical direction. It is however good practice to try and gain the patient’s consent to care in these categories.

5.19.7 Section 62, urgent treatment

Sections 57 and 58 do not apply if the treatment in question is either:

- immediately necessary to save the patient’s life

- a treatment which is not irreversible, but which is immediately necessary to prevent a serious deterioration of the patient’s condition

- a treatment which is not irreversible or hazardous, but which is immediately necessary to alleviate serious suffering by the patient

- a treatment which is not irreversible or hazardous, but which is immediately necessary and represents the minimum necessary to prevent the patient from behaving violently or being a danger to himself or to others

5.20 Mental Capacity Act, guidance assessment of capacity to consent to medication

Appendix H gives information around the gaining of consent under the Mental Capacity Act in relation to the administration of medications.

6 Training implications

There is no specific face to face training on consent; however, consent issues are covered on the following:

- induction programme for medical staff

- training for section 12(2) approved medical practitioners

- Mental Capacity Act training (e-learning and face to face)

- Mental Health Act training

A training needs analysis should be undertaken by the care group management teams to identify the training needs of all staff in relation to consent. Consideration must be given to ensure competencies set meet individual staff needs.

6.1 E-learning consent by staff whose mangers have identified that this is required

- How often should this be undertaken: As identified by service manager.

- Length of training: 60 minutes.

- Delivery method: Module-learning.

- Training delivered by whom: Learning and Development team or ESR.

- Where are the records of attendance held: ESR.

As a trust policy, all staff need to be aware of the key points that the policy covers. Staff can be made aware through a variety of means such as:

- continuous professional development sessions

- daily email (sent Monday to Friday)

- practice development days

- intranet

- team meetings

- local induction

7 Equality impact assessment screening

To access the equality impact assessment for this policy, please email rdash.equalityanddiversity@nhs.net to request the document.

7.1 Privacy, dignity and respect

The NHS Constitution states that all patients should feel that their privacy and dignity are respected while they are in hospital. High Quality Care for All (2008), Lord Darzi’s review of the NHS, identifies the need to organise care around the individual, ‘not just clinically but in terms of dignity and respect’.

As a consequence the trust is required to articulate its intent to deliver care with privacy and dignity that treats all service users with respect. Therefore, all procedural documents will be considered, if relevant, to reflect the requirement to treat everyone with privacy, dignity and respect, (when appropriate this should also include how same sex accommodation is provided).

7.1.1 How this will be met

All employees, contractors and partner organisations working on behalf of the trust must follow the requirements of this policy and other related policies. All health employees must also meet their own professional codes of conduct.

7.2 Mental Capacity Act (2005)

Central to any aspect of care delivered to adults and young people aged 16 years or over will be the consideration of the individuals’ capacity to participate in the decision-making process. Consequently, no intervention should be carried out without either the individual’s informed consent, or the powers included in a legal framework, or by order of the court.

Therefore, the trust is required to make sure that all staff working with individuals who use our service are familiar with the provisions within the Mental Capacity Act (2005). For this reason all procedural documents will be considered, if relevant to reflect the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act (2005) to ensure that the rights of individual are protected and they are supported to make their own decisions where possible and that any decisions made on their behalf when they lack capacity are made in their best interests and least restrictive of their rights and freedoms.

7.2.1 How this will be met

All individuals involved in the implementation of this policy should do so in accordance with the principles of the Mental Capacity Act (2005).

8 Links to any other associated documents

- MCA Mental Capacity Act 2005 policy

- Advance statements and advance decisions to refuse treatment policy

- Resuscitation manual, do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) policy (adults)

- Resuscitation manual

- Interpreters policy (provision, access and use of, for patients, service users and carers)

- Research governance policy

- Electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) clinical guidelines policy

- When a second opinion appointed doctor attends policy

- Community treatment order policy

9 References

- Accessible Information Standards 2015.

- CQC Regulation 11 (2016).

- Department for Constitutional Affairs (2006) A Guide to the Human Rights Act 1998.

- Department of Health Guidance: Seeking Consent Working with Children.

- Department of Health Reference Guide to Consent for Examination or Treatment second addition (2009).

- Department of Health Good Practice in consent implementation guide (2009).

- Equality Act 2010.

- Family Law Reform Act 1969.

- General Medical Council Good Medical Practice (2013).

- General Medical Council 0-18 Guidance for all doctors (2007).

- Human Rights Act 1998, as amended 2005.

- Mental Health Act 1983.

- Mental Health Act Code of Practice.

- Mental Capacity Act 2005.

- Royal College of Surgeons Consent: Supported Decision, Making a Guide to Good Practice (2016).

- The Children Acts 1989 [6] and 2004.

- The Care Act 2014.

- The Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) (amended) Regulations 2015.

10 Appendices

10.1 Appendix A responsibilities, accountabilities and duties

10.1.1 Board of directors

The trust is required to have a policy on consent to care and treatment. It is the responsibility of the board to support the implementation of this policy.

Care group medical directors, care group nurse directors, modern matrons and service managers.

Senior clinical staff must make their staff aware of the consent policy, their adherence to it, including supporting staff to understand the above in relation to their role and service and must monitor its use.

10.1.2 Healthcare professionals

It is the responsibility of healthcare professionals to seek consent to care and treatment and to provide the person with relevant information for them to make an informed decision to consent. The healthcare professional must also be aware of other guidance relevant to their role and or profession.

Health professionals need to understand:

- the circumstances in which verbal consent and written consent must be given and the way this would be documented within their service

- be clear about what is sufficient information to give people in order for them to be in a position to give valid consent within their area of responsibility, this should include how to support people with additional needs to understand information

- how to identify when people are unable to give valid consent

- how to respond to life threating events in their service where consent is not possible

- how to respond to decisions made by people who use services including respecting decisions when they disagree, how to respond when people make decisions which conflict with care, welfare and safety needs

- how legislation relevant to their job would be interpreted in their service

10.1.3 Health and social care staff (support staff)

Healthcare and social care staff must adhere to this policy and inform their managers of any concerns. Seeking consent from patients is a matter of common courtesy between health and social care staff and the patient.

10.2 Appendix B monitoring arrangements

10.2.1 That for detained patients the consent to treatment requirements of the Mental Health Act 1983 are adhered to

- How: Audit of the T2,T3 and section 62 forms.

- Who by: Service managers or modern matrons.

- Reported to: Mental health legislation operational group

It should first be reported to the local mental health legislation monitoring group and then fed into the MHL-OG, which then provides assurance reports into Mental Health Legislation Committee (MHLC). - Frequency: Each completed T2, T3 is audited on completion. A quarterly summary report is then submitted.

10.2.2 The number of reported incidents on the electronic incident report system (IR1) where any issues around consent have been identified

- How: On a case by case basis as the report is submitted.

- Who by: Service managers or modern matrons also be identified within the trust annual summary report.

- Reported to: Quality assurance group.

- Frequency: Annually.

10.2.3 The number of formal complaints received in which any issues relating to consent have been raised

- How: Report.

- Who by: Complaints manager.

- Reported to: Quality assurance group.

- Frequency: Annually.

10.2.4 The number of serious incidents (Sis) in which any issues in relation to consent have been identified

- How: Review of the resulting SI action plan.

- Who by: The relevant care group director.

- Reported to: Quality assurance group.

- Frequency: At the times as identified within the action plan.

10.2.5 That there is a record of each patient’s consent status within their clinical record (within specific audits where consent is specific to the area being audited)

- How: Support care groups with their identified audits.

- Who by: Clinical audit department.

- Reported to: Quality assurance group.

- Frequency: Variable.

10.3 Appendix C guidance, obtaining valid consent patients aged 16 years and over

10.3.1 Valid consent

For consent to be valid it must be voluntary and informed, and the patient consenting must have the capacity to make the decision.

If a patient has the capacity to make a voluntary and informed decision to consent to or refuses a particular treatment, their decision must be respected.

The validity of consent does not depend on the form in which it is given. Written consent merely serves as evidence of consent: if the elements of voluntariness, appropriate information and capacity have not been satisfied, a signature on a form will not make the consent valid.

10.3.2 Provision of information

10.3.2.1 Has the patient been sufficiently informed?

To give valid consent, the patient needs to understand the nature and purpose of the intervention or treatment, the seriousness of their condition and the anticipated benefits and risks of the proposed intervention or treatment and any reasonable alternatives, including the option to have no treatment so they are in a position to make an informed decision. The provision of relevant information is therefore central to the process. Staff should ensure that discussions about consent are in a way that meets the patient’s communication needs. The information must be comprehensible but must be given in a format that will help them understand the specific decision to be made in line with MCA principle 2 and accessible information standards.

When seeking consent, the health professional should check whether the patient has understood the information they have been given, and whether they would like more information and be given sufficient time to use and weigh up the information before making a decision.

Details of any supplementary information provided to the patient such as information leaflets must also be documented on the consent form. Where information leaflets are used from external sources the practitioner must ensure that the leaflets reflect best practice, and the information leaflet version is clearly documented.

10.3.2.2 Duty to inform

Patients will vary in how much information they want; some will want as much detail as possible; others may not ask for any information. However, the presumption must be that the patient wishes to be well informed about the risks and benefits of the various options as clarified in the decision of the Supreme Court on 11 March 2015 in the case of Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board.

10.3.2.3 Material risk

The Montgomery ruling means that

- the doctor is under a duty to take reasonable care to ensure that the patient is aware of any material risk involved in any recommended treatment and of any reasonable alternative or variant treatment, even if the risk is rare

- the test of materiality is whether, in the circumstances a reasonable person in the patient’s position would be likely to attach significance to the risk, or the doctor is or should reasonably be aware that the particular patient would be likely to attach significance to it

- the assessment of whether a risk is material cannot be reduced to percentages. Factors include the nature of the risk, the effect its occurrence would have on the life of the patient, the importance to the patient of the benefits from the treatment, the alternatives available and their risks. The assessment is fact-sensitive and specific to the characteristics of the patient

The general medical council (GMC) guidance ‘Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together’ provides more guidance about the risks (including risk of mortality), benefits and alternatives of any proposed investigation or treatment, presented in a balanced way the patient can understand to help them make informed decisions.

10.3.2.4 The therapeutic exception

The traditional concept of the therapeutic exception (sometimes referred to as therapeutic privilege) describes the situation in which a doctor may claim exemption from the duty to provide certain information to a patient if the doctor deems that this might cause the patient psychological harm to a degree which outweighs the benefits of informing them.

The Montgomery ruling made clear that the therapeutic exception should only be used in rare cases. If it is used the reasons should be documented in the persons’ case notes.

Although the ruling refers to consent obtained by doctors, the same ruling applies to all health professionals when seeking consent.

10.3.3 Capacity to consent, patients aged 16 years and over

When undertaking a discussion about providing care and, or treatment with a patient aged 16 years and over, staff must work on the presumption that they have the capacity to decide what, if any, care and treatment they want to receive (MCA principle 1).

If a patient is struggling with being able to understand the information, the patient should be given appropriate help and support to maximise their ability to enable them to make the decision themselves (MCA principle 2).

10.3.4 Capacity to consent, young people aged 16 to 17 years

Young persons aged 16 or 17 are presumed to have capacity to consent to or refuse care and, or treatment in their own right. Consent will be valid only if it is given voluntarily by an appropriately informed young person with capacity to consent to the particular intervention.

If the 16-to-17-year-old has capacity to give valid consent, it is not legally necessary to obtain consent from a person with parental responsibility. However, it is good practice to involve the young persons’ family in the decision-making if the young person agrees.

Parents cannot override consent or refusal from a competent 16- or 17-year-old.

10.3.4. Lack of capacity, patients aged 16 years and over

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) defines a person who lacks capacity as a person who is unable to make a decision for themselves because of an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain. It does not matter if the impairment or disturbance is permanent or temporary.

Patients may be able to consent to some interventions but not others or may have capacity at some times but not others.

A person’s capacity to consent may be temporarily affected by factors such as confusion, panic, shock, fatigue, pain or medication. However, the existence of such factors should not lead to an automatic assumption that the person does not have the capacity to consent.

Capacity should not be confused with a healthcare professional’s assessment of the reasonableness of the person’s decision. A patient should not be treated as unable to make a decision merely because they make an unwise decision (MCA principle 3).

A person lacks capacity if both:

- they have an impairment or disturbance (for example a disability, condition or trauma or the effect of drugs or alcohol) that affects the way their mind or brain works

- that impairment or disturbance means that they are unable to make a specific decision at the time it needs to be made

An assessment of a person’s capacity must be based on their ability to make a specific decision at the time it needs to be made, and not their ability to make decisions in general. A person is unable to make a specific decision if they cannot do one or more of the following things:

- understand the information given to them that is relevant to the decision

- retain that information long enough to be able to make the decision

- use or weigh up the information as part of the decision-making process

- communicate their decision, this could be by talking or using sign language or other methods of communication

10.3.4.1 Establishing capacity

Where there is no doubt about the patient’s ability to give informed consent there is no requirement to carry out an assessment of capacity.

If there is doubt about the patient’s ability to give valid consent, the health professional must assess the capacity of the patient to take the decision in question. The evidence of the assessment and the conclusions drawn from it should be recorded on the trust MCA1 form and in the patient’s notes. This should include reference to the information given to the patient which is relevant to the decision.

10.3.5 Is the consent given voluntary?

Once it has been determined that a patient has the capacity to make a particular decision at a particular time, a further requirement for consent to be valid is that it must be given voluntary and freely, without pressure or undue influence being exerted on the patient to either accept or refuse treatment. Such pressure can come from partners or family members, as well as health or care practitioners. Patients must not be coerced into consenting, as this would invalidate consent.

Although patients will value in many cases the support of a friend or family member for comfort and help through their decision-making process, it is important to ensure that any decisions represent the patient’s own views and is not unduly influenced by the wishes of another person.

10.4 Appendix D guidance, obtaining valid consent to patients under 16 years

10.4.1 The concept of Gillick competence

Children under the age of 16 years are not automatically presumed to be legally capable of making their own decisions about their healthcare as the Mental Capacity Act does not apply. However, under 16’s may be capable of giving valid consent to a particular treatment or intervention if they have sufficient understanding and intelligence to enable him or her to understand fully what is proposed. This is sometimes known as being Gillick competent. There is no specific age at which a child under 16 becomes capable of consenting to a particular treatment. It depends on the child and the seriousness and complexity of the treatment proposed. The routine assessment of competence in under 16’s should be appropriate to the child’s age.

10.4.2 Gillick competence

Victoria Gillick challenged the Department of Health guidance which enabled doctors to provide contraceptive advice and treatment to girls under 16 without their parents knowing. In 1983 the judgement from this case laid out criteria for establishing whether a child under 16 has the capacity to provide consent to treatment; the so-called Gillick test. It was determined that children under 16 can consent if they have sufficient understanding and intelligence to fully understand what is involved in a proposed treatment, including its purpose, nature, likely effects and risks, chances of success and the availability of other options.

Healthcare professional should not judge the ability of a particular child or young person solely on the basis of his or her age. For a young person under the age of 16 to be ‘Gillick’ competent, she or he should have:

- the ability to understand that there is a choice and that choices have consequences

- the ability to weigh the information and arrive at a decision

- a willingness to make a choice (including the choice that someone else should make the decision)

- an understanding of the nature and purpose of the proposed intervention

- an understanding of the proposed intervention’s risks and side effects

- an understanding of the alternatives to the proposed intervention, and the risks attached to them

- freedom from undue pressure

It is important to give children under 16 appropriate information depending on their age and communication skills. This could include easy read or child friendly leaflets.

10.4.3 Information sharing

Parents generally need to be provided with information about their child’s problems and treatment in order to adequately support and care for them. Check the clinical records to see whether there is evidence of a discussion with the child, and where appropriate their parent(s), about information sharing and confidentiality and the limits of confidentiality. The extent and nature of the discussion will vary according to the age of the child and the nature of treatment as some treatments, for example family therapy, directly involve the parents, whereas others such as medication or individual counselling involve the child. Where information is shared with parents about the problems or treatment of a competent child, the child’s consent to share the information should be obtained and evidence recorded in the notes. The consent should be absolutely clear and should cover the specific detail of what will be shared, the reason the information is being shared, as well as any special aspects of the processing that may affect the individual. It should also be freely given, for example without undue influence from the parents.

Where a competent child refuses to allow information to be shared with their parent(s), there should be evidence that the risks of not sharing the information have been considered. Where it is thought to be in the child’s best interests to share information, there should be evidence of attempts to seek a compromise. It is sometimes possible to provide parent(s) with general information about the treatment or condition as a compromise, rather than the specific details of the child’s case. Where it is the clinician’s opinion that it is necessary to share information in the best interests of the competent child, against their wishes, the Caldicott guardian should be consulted.

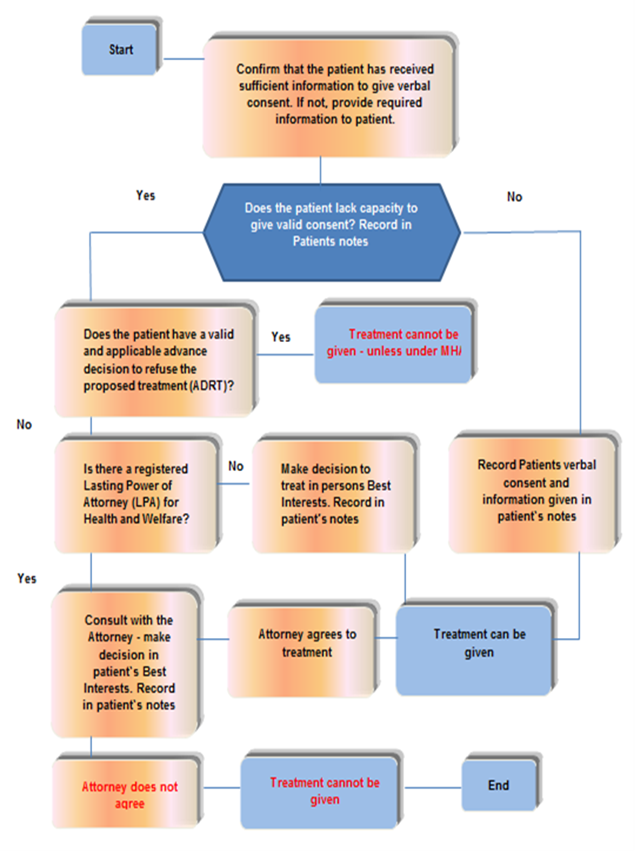

10.5 Appendix E consent flow chart 1, routine care and treatment

- Confirm that the patient has received sufficient information to give verbal consent. If not, provide required information to patient.

- Does the patient lack capacity to give valid consent? Record in patients notes.

- No, record patients verbal consent and information given in patient’s notes, treatment can be given.

- Does the patient have a valid and applicable advance decision to refuse the proposed treatment (ADRT)?

- Yes, treatment cannot be given, unless under MHA.

- Is there a registered lasting power of attorney (LPA) for health and welfare?

- No, make decision to treat in persons best interest. Record in patient’s notes, treatment can be given.

- Consult with the attorney, make decision in patient’s best interests. Record in patient’s notes.

- Attorney agrees to treatment, treatment can be given.

- Attorney does not agree to treatment, treatment cannot be given.

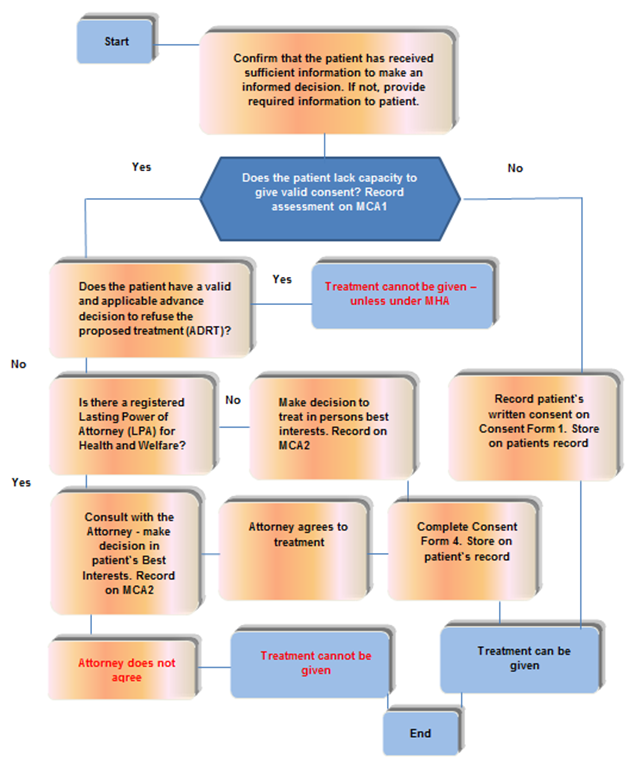

10.6 Appendix F consent flow chart 2, treatment that presents high risk or significant harm

- Start, confirm that the patient has received sufficient information to make an informed decision. If not, provide required information to patient.

- Does the patient lack capacity to give valid consent? Record assessment on MCA1.

- No, Record patient’s written consent on consent form 1. Store on patient record, treatment can be given.

- Does the patient have a valid and applicable advance decision to refuse the proposed treatment (ADRT)?

- Yes, treatment cannot be given, unless under MHA.

- Is there a registered lasting power of attorney (LPA) for health and welfare?

- No, make decision to treat in persons best interests. Record on MCA2. Complete consent form 4, store on patient’s record. Treatment can be given.

- Consult with the attorney, make decision in patient’s best interests. Record on MCA2.

- Attorney does not agree. Treatment cannot be given.

10.7 Appendix G consent forms

To download the trust consent forms click on the relevant link for the form you require:

- Refer to appendix G1: consent form 1 patients aged 16 and over with capacity to consent to care and or treatment or children under 16 with Gillick competence to consent (staff access only).

- Refer to appendix G2: consent form 2 parent (or person who has parental responsibility) agreement to care and or treatment for a child or young person (under 16 years of age) (staff access only).

- Refer to appendix G3: consent form 3 informed refusal (staff access only).

- Refer to appendix G4: consent form 4 patients aged over 16 who lack the capacity to consent to care and or treatment (staff access only).

10.8 Appendix H Mental Capacity Act (2005)

10.8.1 Guidance, assessment of capacity to consent to medication (approved by Dr G. Tosh. Medical Director 15 June 2023)

10.8.1.1 Introduction

It is a general, legal and ethical principle that valid consent must be obtained before providing care and, or treatment (including examination) to a patient. This principle reflects the right of patients to determine what happens to their own bodies and is a fundamental part of good practice.

Care and, or treatment can only be provided to someone with their informed valid consent or with specific legal authority (which may be provided through the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA), Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), Children Act, Common Law etc.).

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) include consent as part of their ongoing monitoring process as part of the “fundamental” standards”. Regulation 11 sections 11(1) to 11(5).

As a provider the trust must make sure that consent is obtained lawfully and that the person who obtains the consent has the necessary knowledge and understanding of the care and, or treatment that they are asking consent for.

Consultation with staff indicates that there is a lack of understanding of how an assessment of capacity should be approached in relation to consent to medication given that a patient could be on several medications for both their mental health and physical health conditions. Also, because a person’s capacity can fluctuate, and their medication regime can change this makes it difficult for staff to understand when to reassess capacity to consent.

The trust consent to care and treatment policy gives guidance for staff around consent to specific treatments which should be referred to, but it was felt that more guidance was needed around recording assessment of capacity to consent to the person’s medication regime.

10.8.1.2 Guidance for inpatient staff

Medication prescribed prior to Inpatient admission.

For those patients who are not detained under the MHA 1983 and who are admitted onto a ward with a number of medications prescribed prior to admission either for physical conditions, or for treatment of their mental health, the prescribing clinician (in the community) should have obtained the patient’s consent at the time when the medication was initially prescribed.

Where the patient has capacity and is consenting to take the medications it would be sufficient to record the details of the medications previously prescribed on the and make a general statement in the patient’s electronic patient record to confirm that the patient is able to give consent to continue taking the medication. Where the patient is unable to consent, consideration should be given whether the medication will continue to be given in their best interest and a general statement in the patient’s electronic patient record to indicate this should be made. For example, existing medication might not be in their best interests to continue if there is a contra-indication with new medication being considered as part of their treatment whilst on the ward.

Where the patient is refusing to take the medication and there are doubts about the patient’s capacity to make decisions about their medication, then consideration of an assessment of capacity would be needed, and the outcome recorded on MCA1.

The assessment of capacity would need to ensure that information relevant to the type of medications is given to the patient and they are able to understand and retain the information to be able to use and weigh up and communicate their decision. They must also understand the consequences of refusal.

If the person lacks capacity to consent to the medication and is refusing, then a best interest’s decision would need to be made, taking into account any advanced statements and advanced decisions to refuse treatment, the views of the person and the views of any interested parties whether the patient should continue to be given the medication. This should be recorded on MCA2. If the person has a valid lasting power of attorney for health and welfare, then consent should be sort from the person(s) with the necessary power to make the decision on the person behalf.

10.8.1.3 Medication prescribed during Inpatient admission, low risk

For any new medication being prescribed by health professionals for minor ailments, such as constipation, coughs and colds, influenza, dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux, irritations to the skin, allergic reactions or mild to moderate pain relief etc, it will not usually be necessary to gain separate formal consent to each medication which is considered low risk to the patient. Such as:

- Aspirin

- Paracetamol or Ibuprofen or Codeine

- Antibiotics

- Cetirizine

- Senna

- Drapolene

- Laxatives

- Simple Linctus

- Peptac or Maalox Suspension

- Bonjela

In many cases, it will be appropriate for a health professional to provide the medication immediately after discussing it with the patient. If the patient is willing for the medication to be given, they will give their consent and medication can be given immediately. It should be noted in the patient’s electronic patient record that the patient is able to give consent as part of their care plan.

Where there is any doubt about a patient’s capacity to give valid consent, to a range of low risk medications for physical conditions they can be grouped together and recorded as one assessment of capacity if they are being prescribed at the same time, providing there is evidence that attempts have been made to make the patient aware of why they are needed and the type and range of dosage likely to be used is recorded on the MCA1.

10.8.1.4 Medication prescribed during Inpatient admission, high risk

For those medications that present a high risk to the patient staff should seek separate assessment of capacity to consent. This includes medication which needs close monitoring or has significant side effects such as:

- antidepressants

- antipsychotics (oral and any IM) such Olanzapine or as Clozapine which has a strict monitoring regime involving the requirement for regular blood tests to be taken

- Lithium which requires monitoring on blood levels, checks for thyroid and renal functioning, Serum calcium levels and blood pressure

- Morphine

- Warfarin

- Thyroxine

- Methadone

- controlled drugs, such as Temazepam, Tramadol, Midazolam, Strong Potassium Chloride Solution BP 15% and Barbiturates

- intra-muscular vitamin supplements

Where there is any doubt about a patient’s capacity to give consent, capacity must be established before the patient is asked to give consent. Details of the assessment of capacity and conclusions reached must be recorded on MCA1. There is no requirement to record multiple MCA1’s to cover, for example, clozapine, lithium, valproate etc, one MCA1 could capture the specific decisions being assessed (consent to mental health drugs clozapine, lithium, valproate etc), but should provide details of the medications being offered.

The assessment of capacity should provide evidence whether the patient is able to understand the nature and purpose of the medication; the seriousness of their condition; the anticipated benefits and risks of the medication or consequences of refusal; and be able to retain, use and weigh up the information and communicate their decision.

If the person lacks capacity to consent to the medication and the medication cannot be provided under the provisions of the MHA, a best interest’s decision would need to be made, taking into account any advanced statements and advanced decisions to refuse treatment, the views of the person and the views of any interested parties whether the patient should continue to be given the medication. This should be recorded on MCA2. If the person has a valid lasting power of attorney for health and welfare, then consent should be sort from the person(s) with the necessary power to make the decision on the person behalf.

10.8.1.5 Hospice, hospice at home

If a patient has a condition that will impair their capacity as it progresses or is otherwise facing a situation in which loss or impairment of capacity is a foreseeable possibility, the healthcare professionals responsible for their care and treatment should encourage them to think about and to discuss their wishes and concerns with the healthcare team as soon as possible whilst they have the capacity to do so.

Where possible staff should seek to develop an advance statement with the patient concerning their medication and treatment pathway that they are likely to receive whilst in the Hospice or receiving Hospice at home services. The patient must clearly articulate the particular care and, or treatments to which they are consenting to.

If the patient does not want to receive a particular treatment, they should be encouraged to write an advanced decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) which can be used at the time should they lack capacity.

If no advance statement or ADRT has been obtained, then staff should follow the principles of the MCA 2005 as above.

Document control

- Version: 10.2.

- Unique reference number: 338.

- Approved by: Clinical policies review and approval group.

- Date approved: 20 February 2024.

- Name of originator or author: Nurse consultant.

- Name of responsible individual: Medical director.

- Date issued: 26 February 2024.

- Review date: 30 April 2026.

- Target audience: All clinical staff.

Page last reviewed: June 13, 2025

Next review due: June 13, 2026

Problem with this page?

Please tell us about any problems you have found with this web page.

Report a problem