What is long COVID and how can it affect me

Long COVID is being recognised widely as a long-term condition. It is diagnosed when symptoms which have developed during or after infection with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks.

There are many different symptoms of long COVID. Research is continuing to enhance our understanding of this condition. We know that symptoms can cluster and change over time.

You are not in this alone. Long COVID is affecting large numbers of patients across the world. Although at this stage we don’t have all the answers, we are seeing people make slow and steady recovery over time. We are here to support you through this journey.

What causes long COVID?

The mechanisms which lead to long COVID are not yet fully understood. We know that the condition can sometimes lead to many of the body’s systems being affected. The condition most commonly affects women, adults aged 35 to 69 years old and people with pre-existing health conditions.

Common symptoms of long COVID

If the respiratory system is affected, you may be experiencing breathing difficulties at rest or when active. You may have noticed that you have developed a dry and persistent cough or a cough which produces secretions.

When the cardiovascular system is affected, you may notice a faster heartbeat and or palpitations. Usually, palpitations are not a cause for concern, but it is sensible to seek medical advice if you are concerned and call 999 if the palpitations or a faster than normal heart rate are accompanied by chest pain, dizziness, or fainting.

The neurological system can be affected, and you may experience brain fog, impaired concentration, short term memory problems, word finding difficulties and sleep disorders. Other common neurological symptoms include pain, headaches, visual disturbances and altered sensations such as numbness or pins and needles.

Where the musculoskeletal system is affected, you may find that you have new joint and or muscle pain since having COVID-19 or pre-existing pain such as arthritis could have been exacerbated by COVID-19.

The digestive system can also be affected resulting in a loss of appetite, weight loss, nausea, acid reflux, abdominal pain, or diarrhoea.

Psychological problems are common and may include anxiety, depression, or post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Ear, nose and throat problems may include tinnitus, dizziness, ear pain, a sore throat, voice changes, loss of taste or smell.

Dermatological problems can include skin rashes, itchy skin, and hair loss.

What kind of recovery can I expect?

Most of the people we see make a good or full recovery from their symptoms. We find that treating and improving one or two of the key symptoms can often improve a number of other symptoms.

Recovery isn’t always linear. Symptoms can remit and relapse making recovery inconsistent at times. Symptoms can come and go, and new symptoms can sometimes develop.

What we know is that returning to work or physical activity too early in your recovery can sometimes result in a more prolonged recovery period. It is vital that we stress the importance of pacing yourself to prevent post exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE).

Good breathing habits, pacing yourself, relaxation and maintaining a positive attitude are key factors which can help with your ongoing recovery.

Fatigue

Fatigue can be a normal part of the body’s response to fighting a viral infection. It is not uncommon for the fatigue to linger after the initial infectious period has ended.

Primary fatigue is related to the pathology of the condition (virus), secondary fatigue is related to other factors or triggers such as overdoing it.

Post viral fatigue is different to everyday tiredness and has been described as feeling as though someone has pulled the plug out on my energy.

Fatigue does not affect everybody in the same way and everyone’s personal experience will differ.

It is known to have an impact on day-to-day life including work and personal life, it can be unpredictable and is known to have periods of relapse and remit in symptoms.

Fatigue can impact us physically, mentally, and emotionally, affecting how we think, what we do and how we feel.

Fatigue is caused by an interruption to our nervous system.

The nervous system is made up of two parts:

- central nervous system, which consists of the brain, spinal cord and nerves, this controls conscious actions, for example, reaching out to pick up a fork to eat your dinner

- the autonomic nervous system, controls ‘automatic’ processes in the body that we are not aware of, for example, blood pressure regulation, temperature regulation, breathing rate (among others)

Post viral fatigue is known to affect the autonomic nervous system.

The autonomic nervous system

- Has two parts.

- Controls the fight or flight response, which causes issues with dysautonomia response (sympathetic nervous system).

- Controls the rest and digest response (parasympathetic nervous system).

- These parts are usually fairly well balanced.

What is dysautonomia?

Is felt to be responsible for triggering many of the symptoms of long COVID.

The body remains in fight or flight mode after the initial infection has gone. The body is almost on alert looking for any other dangers or threats that may be coming and almost loses its ability to switch off and relax.

This can throw many of the body’s systems out of sync, for example, increased need to urinate, difficulty regulating body temperature, breathing pattern, heart rate etc.

Post exertional malaise (PEM)

Is a marked rapid physical or cognitive fatigue in response to exertion and increased activity. Often a delayed onset can occur 24 to 72 hours after the activity and exertion, hence the importance of monitoring activity and fatigue levels. It can result in both physical and mental symptoms such as poor concentration, difficulty in thinking, flu like symptoms (muscle aches, pains, headaches, and sore throat). It can cause increased difficulty in sleeping and also orthostatic intolerances (issue balancing blood pressure and heart rate when standing upright).

How to recognise fatigue onset

Good management of fatigue requires a variety of strategies in order to recognise any contributing factors and triggers. Common things that our service users report are:

- feelings of extreme tiredness or complete lack of energy

- inability to complete activities

- muscle aches and joint pains

- reduction in appetite

- mental fatigue, such as issues with concentration and memory (brain fog)

- difficulty communicating or word finding

- mood changes such as increase in anxiety levels or irritability

Maintaining activity

All activities that we do are composed of many skills: physical, cognitive, psychological, and interpersonal. In everyday life, we often complete activities without having to really think about what we are doing.

For us to complete what might seem like a simple activity, such as making a cup of tea, lots of different skills are required, all of which use up our energy to different levels.

Use the 3Ps

Planning, how can you spread your activities out over the day and week?

Can higher energy tasks be carried out at a different time? Thinking through activities before you do them, could they be done differently to make them easier and therefore less strenuous?

Pacing

Looking at your diary and identifying how activities can be broken up rather than being done all in one go. Finding your baseline level (a level which you are comfortable at and can complete without fatigue) and ensuring that you have a middle ground of not doing too much or too little. Ensure that you incorporate rest periods in between activities to help recharge.

Prioritising

- What is necessary, and what could wait?

- What do I want to do today, and what do I need to do today?

- Could the task be carried out by someone else could they help me?

What you can do to help

- Complete diaphragmatic breathing exercises.

- Mindfulness and meditation.

- Guided relaxation.

- Gentle exercise such as yoga and Tai Chi which is very useful for managing breathing.

- Other activities that you find relaxing, for example, listening to calming music.

Fatigue patterns

Fatigue is a common symptom following infection with COVID-19. Fatigue can also be more significant if your body has become deconditioned due to being less active than normal. Inactivity can commonly cause stiff and painful joints and muscle weakness.

If you are experiencing breathlessness or feelings of stress and anxiety, these factors can also increase your fatigue.

Fatigue can affect us in different ways, it can cause us to feel discomfort or pain, general weakness, anxiety, difficulty with memory and concentration, tearfulness and frustration.

There are many things that you can do to help with your fatigue levels, but first it is helpful to know which activities may be triggering your fatigue in order to identify patterns.

Some activities will require more exertion than others and it may be that these activities need to be spread out over your week to help you to pace yourself.

To give you an idea, some examples are below.

| Red activities | Amber activities | Green activities |

|---|---|---|

| Taking a shower | Walking up and downstairs | Making breakfast |

| Vacuuming the house | Loading the dishwasher | Having a phone conversation |

| Gardening | Driving | Cooking a meal |

| Jogging | Walking the dog | Attending an appointment |

These are just examples, when you start to fill in your own diary and scores, you will build up a picture of the activities which have the most impact on your energy levels and which may be triggering your fatigue (these are your red activities). Once you can see this pattern and the triggers, try to space these red activities out over the week so that you reduce the amount of red activities you do in the same day or consecutive days. You may need to do the same with the amber activities, depending on your levels of fatigue.

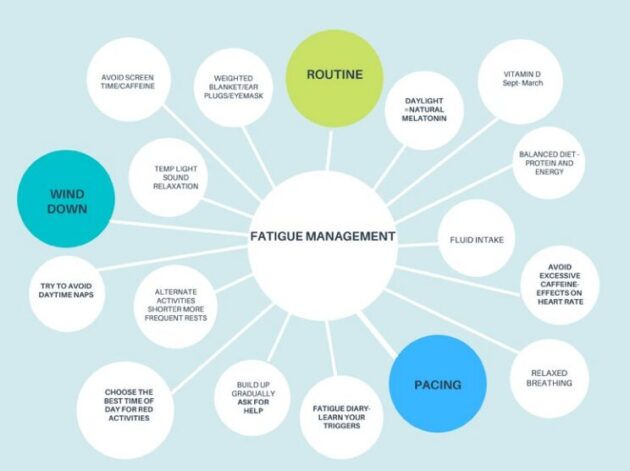

Fatigue management:

- routine

- pacing

- wind down

- avoid screen time or caffeine

- weighted blanket, ear plugs, or eye mask

- daylight, natural melatonin

- vitamin D, September to March

- temperature, light, sound relaxation

- balanced diet, protein and energy

- fluid intake

- if you need daytime naps, set an alarm to prevent sleeping for too long

- alternative activities shorter more frequent rests

- avoid excessive caffeine effect on heart rate

- relaxed breathing

- choose the best time of day for red activities

- build up gradually ask for help

- fatigue diary, learn your triggers

Managing breathlessness in long COVID

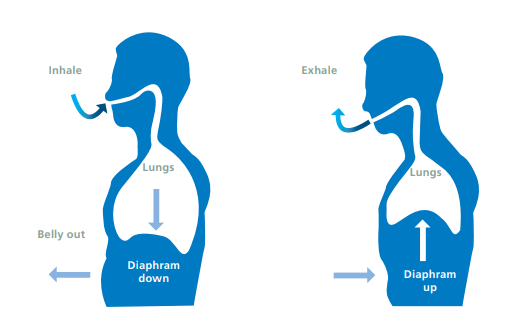

What does normal breathing look like?

As you take a breath in, the diaphragm (the dome shaped muscle underneath your lungs) contracts and flattens, this allows the lungs and ribcage to expand.

On breathing out, the diaphragm relaxes and returns to its normal dome shape, allowing air out of the lungs, causing the ribcage to relax again.

Normal versus abnormal breathing

| Normal breathing | Abnormal and dysfunctional breathing |

|---|---|

| Respiratory rate around 12 breaths per minute | Increase or a decrease in the respiratory rate |

| Nasal breathing (in and out via the nose) | Mouth breathing (can often be noisy) |

| Belly (diaphragmatic) breathing | Shorter, more shallow breaths from the upper chest with lots of shoulder movement |

| Pause in between breaths | No pause between breaths |

Common causes of breathlessness in long COVID

- Development of a breathing pattern dysfunction (BPD).

- Reduction in respiratory muscle strength.

- Disruption to the autonomic nervous system.

- General deconditioning and reduction in exercise tolerance.

- Anxiety.

Normal breathing process

- Inhale into lungs.

- Diaphragm goes down.

- Bell goes out.

- Belly goes in.

- Diaphragm goes up.

- Exhale out of lungs.

Positions of ease to help with breathlessness

Leaning forward is the optimal position to be in to aid with relieving shortness of breath. You can either do this in sitting or standing.

- Sat leaning forwards on a chair.

- Stood leaning forwards against the back of a chair.

- Sat leaning forwards on a chair with your head rested against a table with a pillow.

- Stood back against a wall.

Breathing exercises to try

Respiratory muscle training

- Start with laying on your back and begin to notice where your breath is coming from.

- Focus on breathing into your belly, so that your abdomen rises and falls as you breathe in and out. You can place a hand on your belly just underneath your ribs to provide some physical feedback as to where you should be breathing from.

- Take gentle breaths in and out through your nose.

- Regular practice of this will improve breathing efficiency.

Light, deep, slow breathing technique

Breathing light (biochemistry)

Make yourself comfortable and try to be somewhere quiet so that you feel relaxed. Try laying down when you first start to practice this.

Breathe in and out through your nose for five minutes. If you need to stop at times to regulate breathing through your mouth, that is fine, do this, and return to nasal breathing.

Now try to take in slightly less air with each breath in to create a light air hunger (the urge to breathe in more air).

Slow the breathing and quieten the breathing. Closing your eyes can help you to focus on this and calm the mind. You should notice that the breath in is shorter than the breath out. There should be a brief pause between breathing out and breathing back in again. Practise for four minutes in total if you can. If air hunger becomes too uncomfortable stop for 30 seconds, breathe normally and start again.

A feeling of air hunger is the urge to breathe in more air. It shows that the exercise if being done correctly, but if this is too uncomfortable, rest breathe normally and try again.

Breathe deep (biomechanics)

Continue breathing light as you have just done. Now relax the head and shoulders and place one hand over the diaphragm (over the upper tummy). As you breathe in, feel the tummy rise outwards and away. As you breathe out, feel the tummy fall back inwards. Continue for approximately four minutes. Remember to breathe light, and quiet through the nose, sipping the air in and gently breathing back out.

Breathe slow (cadence)

If you manage the above techniques, you could try to progress to this final stage:

Slow your breathing down to four seconds in and six seconds out. If air hunger is too much you could modify this to three seconds in and four seconds out to begin with and the aim to progress to four seconds in and six seconds out.

Note, if you have already been given breathing exercises by your physiotherapist, please let us know as the cadence may be slightly different for you.

Relaxation

Relaxation is when the body and mind are free from tension and anxiety. Sometimes we need to learn how to relax and explore ways of helping ourselves to reach this tension free state of being.

Physical and emotional stresses can have an impact on our physical and mental health. Other priorities in life can take over and sometimes we think of others and do not stop to think of ourselves.

If we don’t look after ourselves, we will eventually experience burnout and we lose our physical and emotional resilience.

Why is relaxation important to long COVID recovery?

Relaxation is important for everybody and can be a powerful tool to help to improve wellbeing.

Learning how to relax effectively can influence many of the symptoms that people with long COVID are experiencing. It can help with breathing control, reduce muscle tension, reduce anxiety, and influence our mood. Relaxation can help to reduce fatigue and brain fog. It can aid digestion and build resilience to allow us to manage everyday stresses more effectively and with less harm to our mental health.

Little tips

Take a pause and practise mindfulness, try pausing through the day for five minutes each time, clear your head and try to be mindful of your breathing, your body and your environment.

Stop rest reset allow yourself rest breaks through the day, plan something rewarding for yourself every day. This could be sitting in the garden with no interruptions, reading a good book, having a walk to engage with nature.

Take control of draining thinking habits: if you have negative thoughts, ask yourself if the thought is helpful, is it factual or just hypothetical. If the thought is unhelpful or not factual discard it and let it go.

Reduce your reliance on electronic devices, even half an hour away from mobile phones, laptops and tablets can be liberating.

Relaxation techniques

Breathing control is always a good place to start when learning how to relax. Practising light slow and deep breathing in and out through the nose for 10 minutes twice a day is a proven and recommended technique. You may have been shown this technique by your physiotherapist.

Meditation and relaxation apps which include slow soft melodies or nature sounds can be calming when trying to relax and can be used effectively with breathing control.

Gentle exercise such as Tai Chi, Yoga and stretches are great for relieving tension. This kind of activity can also release endorphins which increase feelings of pleasure and wellbeing and can help to reduce discomfort and pain.

Other more structured techniques include progressive muscle relaxation and guided visualisation. You may have been taught these as part of your therapy programme with the long COVID team. There are many different ones to try, or you could create your own.

Below is an example of a structured relaxation technique.

Progressive muscle relaxation (15 to 20-minute session)

Progressive muscle relaxation is an exercise which helps us to relax any physical tension in the body and helps us to calm our thoughts.

In doing this, the effects can have a calming influence on our nervous system, which in turn helps us to control our breathing, heart rate and regulate our emotions.

During the following series of muscle tensing activities, you will need to tense each muscle in turn and then gently let go of that tension. Throughout this exercise it’s helpful if you can visualise the muscles when you are tensing them and then appreciate the sensation of letting go of the tension. Let this sensation wash over you as you let go of the tension each time.

Throughout this exercise take steady controlled breaths in and out through the nose at all times if you can.

Make sure the position you are in is comfortable, find a better position if you need to.

Now close your eyes or if you don’t feel comfortable to do this, just lower your gaze. Allow your attention to focus only on your body. If you find your thoughts wandering, bring your attention back to the muscles you are working on.

- Place one hand onto your tummy. Take a slow breath in through the nose so that you feel your tummy rise and visualise the air filling the lungs. Now slowly and gently breathe all the air back out again through the nose. Continue this controlled breathing, in through the nose and slowly breathe out through the nose. As you breathe in, visualise the lungs filling with air and as you breathe out feel the tension leave the body and clearing the thoughts in your mind.

- Try to make sure you continue with this good steady breathing pattern.

- Starting with the head and face, tighten the muscles just above the eye sockets into a frown, hold for a count of five, and then slowly let go to smooth the forehead back out again. Feel that sense of letting go as the tension falls away (10 seconds pause).

- Tighten the muscles around the eyes by pressing your eyelids tightly shut, hold for a count of five and then keeping your eyes closed let go of the tension. Take a moment to appreciate the softness in the muscles in the face (10 seconds pause).

- Let the tongue fall away from the roof of the mouth and let it settle, without tension, breathing in and out through the nose (10 seconds pause).

- Gently tilt your head back, hold for a count of five and let go. Breathing in and out through the nose.

- Now take a moment to feel the weight of the head and neck as the head sinks down into a position of rest and relaxation.

- Let go of any tension.

- Now raise the shoulders up towards the ears, hold for a count of five and slowly release. Feel the shoulders fall into a position of rest and allow any tension to flow away. Feel the heaviness of the shoulders (10 seconds pause).

- Moving down to the hands.

- Slowly clench the left hand into a gentle fist and hold this position for a count of five and now release. Feel the wrist and the fingers and thumb settle back into a soft position, resting on the surface they are in contact with.

- Slowly clench the right hand into a gentle fist and hold this position for a count of five and release. Feel the wrist, the fingers and the thumb settle back into a soft position, resting on the surface they are in contact with (10 seconds pause).

- Breathing in and out through the nose. Visualise the air filling the lungs and as you breathe in. As you breathe out visualise all tension leaving the body (10 seconds pause).

- Now bend the elbows and tense the biceps muscles, hold for a count of five and slowly let go.

- Now straighten the elbows and tense the muscle at the back of the arms, hold for a count of five and slowly let go.

- Expand the chest, by taking a deep breath in through the nose, hold for a count of five and breathe out slowly, breathing tension out all the way (10 seconds pause).

- Slowly stretch the bottom of the back by arching back, hold for a count of five and slowly let go.

- Feel the heaviness of the upper body, the head, the shoulders, the arms, the hands, the fingers (10 seconds pause).

- Tense the muscles in the front of the thighs by pushing down into the surface you are resting on, hold for a count of five and slowly let go.

- Now flex your feet, pull your toes up towards you to feel the tension in the calf muscles at the back, hold for a count of five and let go. Feel the legs sink down, heavy against the floor (10 seconds pause).

- Curl the toes, hold for a count of five and let go.

- Now let the whole body sink down into the surface that is supporting you.

- Focus on your breathing, breathe in for three, breathe out for four, breathe in for three, breathe out for four. Visualise an inner warmth slowly spreading through the body, starting at the head, slowly, gradually moving all the way down to the feet (10 seconds pause).

- Feel the weight of a relaxed body (10 seconds pause).

- Now try breathing in for four, breathing out for six, in for four, out for six (20 second pause).

- Now slowly open your eyes, stay still and relaxed, breathe in for four and out for six.

- In your own time you can get up. Be aware that you may feel a little dizzy so get up slowly and make sure you feel okay before standing.

What is mindfulness?

Put in its most simple form, it is to have awareness. Its paying attention on purpose. Mindfulness is a way of cultivating an awareness of one’s thoughts, feelings, both physical and emotional, perceptions and experiences, in a non-judgemental way. This can be carried out through both formal and informal practice.

Through formal practice we can focus fully on the breath, the sensations we experience, both physical and emotional, the thoughts that arise, and we can learn how to deal with and process those thoughts and feelings. Through informal practice we can truly experience daily events that might otherwise go unnoticed when we are on autopilot mode, such as the sound of birds singing, the colour of the trees, the taste of an apple, or the feel of the soap on our hands as we wash them.

Through this practice of observing ourselves, with a holistic approach, we learn about our own thought patterns and emotions. We can identify where in our body we feel them, and how we react to them. With continued practice of observing without judgement, we can start to become more familiar with these feelings and give ourselves the freedom of choice. To choose how we wish to respond and react to whatever may arise.

Mindfulness is a wonderful way to learn how to relax. It can also help with many physical and emotional disorders including depression, anxiety, pain and stress.

Examples of informal mindfulness meditation:

- enjoy a meal mindfully, notice the colours, the smell, the texture, and the flavour

- have a mindfulness shower, have complete awareness of the sensation of the water on your body, the temperature, the feel of the lather on your skin and hair, the fragrance of the shampoo

- go for a mindful walk, really notice the colours of the trees, flowers, and sky, the scent of the grass, the sound of the birds singing, the feel of the sun or wind on your skin

- do something you enjoy mindfully, gentle movement, yoga, Tai Chi, jogging, golf, coffee with friends, whatever you enjoy, do it mindfully, with complete awareness

Examples of formal mindfulness meditation:

- focus on your breath, in sitting or lying, focus on the sensation of each in and out breath, if the mind wanders, notice and kindly return to the breath

- allow thoughts to drift by, practice observing the thoughts that arise whilst focusing on the breath, and imagine them floating by like a cloud in the sky, or a helium balloon floating away

- follow a guided meditation, where your mind will be guided to focus on the breath, body, or surroundings

- follow a guided visualisation, where you will be invited to create a scene in your mind to explore your thoughts and feelings

Sleep

Sleep disturbance in long COVID is a common and debilitating symptom.

Some people have difficulties getting to sleep and others have problems reaching the deeper phase of sleep or staying asleep. This can be due to many reasons, including joint and muscle pains, feeling anxious, having an inefficient breathing pattern or an overactive racing mind.

We know that breathing well during the day can help to make your night time breathing pattern more efficient. This can promote a more restful sleep pattern and reduce insomnia.

Maintaining a routine helps to maintain the body’s natural daytime and night time rhythms. Waking and going to bed at the same time each day will help with this pattern and help with sleep.

Natural daylight also affects our body rhythms, our mood and sleep. Getting natural daylight every day helps in the production of hormones which help us to maintain a regular body clock and helps to promote good sleep. Spending some time outdoors or if at work, sitting next to a window can help with this natural light exposure.

If you use a computer all day for work, wearing blue light filtering glasses will help to reduce eyestrain and headaches which can also help with sleep.

Long daytime naps should be avoided if at all possible as this can result in a reversed sleep pattern where the body wants to be awake during the night.

If joint or muscle discomfort is a problem, trying new sleeping positions and using pillows to support the hips and legs can help. Body pillows are often a useful option so that when you are laying on your side the hips are maintained in a neutral resting position.

The winding downtime before bed is important, avoiding screen time, alcohol, and caffeine for a good couple of hours before bed and taking a warm bath are all different ways which can help to relax the nervous system.

Ear plugs, eye masks and weighted blankets are things which you could try to promote a more restful sleep. You could also turn your mobile phone onto silent or flight mode, your alarm will still work if you use an alarm on your phone to wake you.

If you are waking during the night with difficulty getting back to sleep, try to bring your attention to your breathing. The main breathing muscle (the diaphragm) is connected to the vagus nerve which releases a calming chemical in the body, this chemical slows the heart rate, so slow tummy breathing can calm the mind and help reduce anxieties and feelings of panic.

Slowing the breathing rate down can activate this relaxation response which then reduces the heart rate and rebalances the nervous system.

If the above techniques do not help you could talk to your local pharmacist about over the counter herbal sleeping tablets. As a last resort when all other options have been tried, GPs will sometimes prescribe medication when sleep disturbance remains debilitating and is impacting on fatigue and everyday life.

Returning to activity

Maintaining activity following illness is important for health and wellbeing.

Being active helps to reduce the risk of illness, it increases muscle strength, it can improve cardiovascular fitness, joint flexibility, and mental health.

With a condition like long COVID where fatigue can be a dominant symptom it is important to remember the three Ps:

- planning

- prioritising

- pacing

It is important to monitor your symptoms including your fatigue levels and breathlessness and you can also monitor your heart rate if you feel this is helpful. Using tools including activity diaries, fatigue diaries, the BORG breathlessness scale (see diagram), can help you to monitor the effects of activity and also allow you to see progress.

Activity diaries, note your breathlessness during and after activity.

Fatigue diaries, track your fatigue levels and pace back as needed.

BORG breathlessness scale, aim to be working at 6 out of 10 with good breathing control and be able to hold a conversation.

Watch device and heart rate monitor, if you are struggling with tachycardia (increased heart rate) you can monitor the effects that activity or exercise is having on your heart rate. This can help with pacing yourself and slowing down when you need to.

Remember that fatigue symptoms can be exacerbated if activity and exercise levels are too high to begin with.

Borg 1 to 10 rating of perceived exertion scale

- Rest

- Really easy

- Easy

- Moderate

- Not so hard

- Hard

- Really hard

- Really, really hard

- Maximal, just like my hardest race

Chest discomfort

Some people may experience some chest tightness or pain during exertional activities. This can understandably be worrying as you may think your heart is ‘damaged’. Most of the time this is nothing to worry about and is often due to weakness of the respiratory muscles and surrounding soft tissue.

Call 999 if:

- you have sudden onset chest pain that radiates to arms, back, neck or jaw

- pain that is sudden tightness or heaviness in the chest

- sudden shortness of breath that is associated with sweating and nausea or vomiting

Everyone is different and at different points in their recovery, so it is important to be mindful of where you are at and try not to do too much too soon. Being realistic with your expectations can also help you to set achievable goals.

Remember that it may take a while to get back to your pre-COVID-19 fitness levels.

Starting activity with caution

- Begin with a short walk on the flat, daily (10 minutes).

- Increase the time and distance weekly until this is doubled, as long as fatigue allows. Continues to monitor fatigue or symptoms.

- Return to your original starting distance, complete twice daily (10 minutes, 2 times daily).

- Gradually increase these walks weekly again until doubled in time or distance.

- Slowly increase the pace of your walk at a comfortable pace, ensuring you are not having issues with post exertional fatigue.

Stretching exercises

Can help to improve muscle tightness, joint flexibility, joint strength and can help with relaxation and anxiety.

Tai Chi is also a very gentle way of exercising to help to restore movement. This is a link which you can use at any time to watch and join in with some of the movements. See helpful Tai chi video (opens in new window) for this.

Links to other services and groups in Doncaster

Long COVID relaxation videos

Document control

Document reference: DP8761/09.22.

This information is correct at the time of publishing September 2022.

Page last reviewed: December 23, 2024

Next review due: December 23, 2025

Problem with this page?

Please tell us about any problems you have found with this web page.

Report a problem