Why am I still breathless after COVID?

Breathlessness is the second most common symptom of long COVID. There are several reasons why this happens.

- Deconditioning, you may have become less active while you were recovering from COVID. Inactivity and weight gain can result in body deconditioning. This can mean that you become breathless when doing the slightest activity such as doing housework or climbing the stairs.

- If you had developed pneumonia when you had COVID this can sometimes leave you with breathlessness.

- Breathing pattern disorders (BPD) are commonly seen in people recovering from COVID and other illnesses. This happens when poor breathing habits are formed.

- Anxiety or a traumatic past event can trigger a BPD and breathlessness.

- Reflux disease can cause breathlessness, coughing, and voice changes.

Being breathless can be a worrying feeling but the good news is that there are techniques which your clinician can show you, to help you to restore good breathing control and help you to return to better health.

Good breathing has many health and wellbeing benefits including improving our energy levels, restoring good sleep, improving concentration, improving exercise tolerance, and helping with anxiety.

Before we look at the techniques, we first need to understand what a normal breathing pattern is:

Normal breathing (good breathing)

Nose breathing

A good breathing pattern starts with the nose. The nose has an important role to play in breathing control:

- it warms and humidifies the air we breathe in

- it filters the air that we breathe in and in doing this it helps to protect the lungs from foreign particles such as dust, virus particles and pollen

- it produces a gas called Nitric Oxide which mixes with the air we breathe in, and this helps to neutralise any harmful particles we breathe in. Nitric Oxide also helps with the transfer of oxygen into the blood steam

- it regulates air flow to the lungs so that we breathe in the correct volumes of air, this helps to prevent over breathing

- it lowers the risk of snoring

- it prevents a dry mouth, dry coughs, sore throats, and recurrent infections

- it helps with tummy breathing so that we use the diaphragm muscle for efficient breathing (this is the main muscle we should use for breathing)

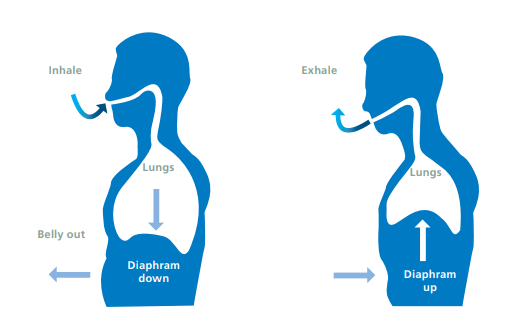

Breathing from the tummy

The diaphragm is the main muscle we use for breathing. This is a dome shaped muscle which sits just below the lungs. When we breathe in, the diaphragm muscle contracts to moves downward to increase the capacity of the rib cage and lungs. The lungs can then expand and fill with air.

When we breathe out the muscle relaxes to its original dome shaped position as the air leaves the lungs. You can check if you are tummy breathing by resting a hand over the upper abdomen. As you breathe in the tummy should rise outwards and as you breathe out the tummy should relax back in.

Rate and rhythm of breathing

When we breathe correctly using our nose and tummy, this helps to regulate the air flow into our lungs and helps us to breathe slow, smooth, and rhythmical breaths. The out breath should be longer than the in breath. After the out breath there should be a comfortable and natural pause before the next in breath.

So, what happens with a breathing pattern disorder?

- Instead of breathing from the nose, you may notice that you breathe from the mouth.

- Instead of breathing from the tummy, muscles in the neck and upper chest are used.

- These changes in the breathing pattern cause shallow and fast breathing (known as over breathing or hyperventilating).

- The in and out breath are the same length.

- These is no pause after the out breath.

- You may feel a sense that you need to take in more air (this is called air hunger).

- You may notice other things including yawning, sighing, gasping, and clearing the throat (these can be common signs of air hunger).

What can I do to help my breathing?

Breathing awareness

Your clinician will assess your breathing and guide you to be more aware of your breathing pattern. This is also a useful technique for you to use, to check in with your breathing during times when you may feel more breathless or anxious.

- Sit in a comfortable position, placing one hand lightly on the upper chest and one hand over the tummy.

- Do your neck, shoulders or chest feel tight?

- Pay attention only to your breathing. You may need to close your eyes to do this.

- Do you breathe in and out through your mouth or your nose?

- Is your nose congested?

- Do you breathe using the upper chest or the tummy?

- Can you hear your breathing or is your breathing quiet or silent?

- Is your breathing fast and erratic or slow and smooth?

- Is there a natural pause after the out breath?

Your clinician will discuss how you felt during the breathing awareness exercise.

What if I have nasal congestion?

Sometimes people find nose breathing difficult because the nose is congested, or one nostril may be narrower than the other. A common cause of congestion is Sinusitis where the lining of the nose and sinuses becomes inflamed (or swollen). This swelling causes mucus to become trapped in the tiny hairs in the nose. Allergens such as pollen or dust can cause this.

A nostril may be narrowed because of nasal polyps. These are an overgrowth of the lining of the nose. Another cause of narrowing is a deviated septum. This is a change to the structure of the nose, which you may have had from birth or due to trauma.

Any of these problems can cause us to breathe through the mouth as this feels easier. However, the less you use the nose the more congested it will become and likewise the more you use the nose, the clearer it will become.

There are also quick and effective techniques which your clinician can teach to you to help to alleviate nasal congestion and restore nose breathing.

Buteyko nose clearance techniques

Nodding, repeat 10 times

Please do not try this technique if you have problems with the joints in your neck.

- Breathing through your nose, slowly nod your head backwards and forwards.

- Your neck muscles need to be relaxed.

- Never force the movement.

- Breathe smoothly, gently, and as quietly as possible through the nose.

Slowly coordinate the movement with your breathing. Breathe in as your head goes back and breathe out as your head goes forward.

Hold and blow, repeat three to six times as advised by your clinician

Please do not try this technique if you have problems with your ears or if you have ear nose or throat infections.

- Take a normal breath in and out.

- Hold your nose.

- Increase the pressure at the back of your nose by gently trying to blow through your nose while still holding it closed for a count of five.

- You may feel your ears pop.

- Don’t allow cheeks to puff out.

- Release your nose and breathe in and out gently through your nose.

- If one nostril remains blocked, release the blocked nostril, and try to breathe in and out gently through the one which is more blocked.

- Repeat the technique two to three times as needed.

Other things to try for nasal congestion

Saline nasal sprays can help to ease congestion. They help to wash and clean the nasal cavities of debris. These can be bought at your local pharmacy.

Antihistamines can help if the congestion is being caused by an allergen. These can be bought at your local pharmacy.

Where nasal congestion is persistent despite trying the above exercises and techniques, you could speak to your local pharmacist or GP about trialling a steroid nasal spray.

Where there are structural changes to the nasal cavity, from polyps or a defect, your clinician in long COVID Clinic may refer you to your GP or ear nose and throat clinic.

The following link may be useful to watch the videos on breathing and nose clearance, Buteyko breathing (opens in new window).

Learning breathing control

- Sit in a supported comfortable position with the legs uncrossed or lay if you prefer.

- Check your posture and relax any muscles which feel tight. You may need to relax the neck, the jaw and you may need to drop the shoulders.

- Place a hand lightly over the tummy.

- Close the mouth.

- Breathe in through the nose and feel the sensation of the tummy rising outwards.

- Breathe out through the nose and feel the tummy gently lower back in as you relax.

- Wait for the next breath to come before breathing back in. This pause should be held without tension.

- Focus only on your breathing and clear your mind.

- Your breathing should be quiet, soft, slow, smooth, and rhythmical.

- Continue to breathe in and out through your nose, feeling the tummy rise and fall.

Once you can maintain nose breathing for five minutes, your clinician may set you a target of slowing your breathing down further:

- try to slow your breathing to three-three-one (in for three, out for three, pause for one)

- if this is easy for you, try progressing to four-five-one (in for four, out for five, pause for one)

Increasing the duration of the out breath has an important part to play in relaxation. It helps to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, this is the part of our nervous system which helps us to rest, relax and overcome anxious feelings and panic.

You may find a metronome app useful for timing your breaths. Or it may help to coordinate your breathing by visualising a relaxing situation, for example being on a beach and as you breathe in and out, imagine the waves lapping into shore and then

Try to practise this technique twice a day for five minutes each time. If this is difficult, try one minute at a time, and gradually build up to five mins twice daily. Practising will help you to gain more control over your breathing and reduce air hunger. You will then be on your way to correcting your breathing pattern disorder.

Rectangle breathing

This is another way you can visualise a more normal breathing pattern. If you feel anxious find a rectangle to look at. This could be a window. Breathe in on the vertical and out on the horizontal and so on.

Breathlessness on activity

Breathlessness can begin with little warning and sometimes come on quickly during activity or exercise. You may find that symptoms may be triggered by things like walking uphill, coughing, or even talking on the telephone. Sometimes you may even be holding your breath due to the effort of a task and then notice on finishing the task that you cannot get your breath.

All these situations can cause you to over breathe.

If you have a ‘trigger’ activity such as climbing stairs, try pausing on the stairs before the breathlessness starts to take over and try the following Buteyko technique:

Buteyko mini pauses rescue technique

- Take small “mouse” breaths through your nose in the following sequence:

- breathe in, out, pause for one count

- breathe in, out, pause for two counts

- breathe in, out, pause for three counts

- breathe in, out, pause for two counts

- breathe in, out, pause for one count

- As you become confident with this technique, you can increase the length of the sequence and hold the pauses for longer.

- You can repeat the mini pauses for up to five minutes. If you take a reliever inhaler and still feel breathless after the mini pause set, then use your reliever inhaler as normal.

You can find out more at Buteyko breathing (opens in new window)

Another technique that can help with maintaining breathing control during activity is blow as you go. Try breathing in through the nose before making the effort and breathe out fully during the effort. Sometimes people find it helpful to use pursed lips to blow the air out through the mouth.

It is normal to become breathless when we are active or exercising. Your clinician can work with you to find an appropriate level for you to work at while maintaining good breathing control. The intensity you can safely exercise at will depend on the stage of your recovery.

Being less active than normal for a prolonged period due to illness, can result in significant muscle weakness and stiffness in the joints of the body. This can make exercising difficult at first. Exercise is important for rebuilding strength and endurance, and this needs to be done safely and at the right level for you, to prevent making any other of your symptoms worse. Your clinician can advise you on the safest approach to being more active or resuming exercise. If you have fatigue, it is important that exercising doesn’t cause you to crash or relapse (also known as post exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE).

The Borg is a useful tool used by clinicians to help you to rate your breathlessness and to work within a safe and manageable level as you return to activity and exercising. Your clinician will assess your level of exercise tolerance and advise which level to aim to work at using this scale.

Borg 1 to 10 rating of perceived exertion scale

- Rest

- Really easy

- Easy

- Moderate

- Not so hard

- Hard

- Really hard

- Really, really hard

- Maximal, just like my hardest race

Positions of ease to help with breathlessness

The following positions can help you to recover when you are feeling breathless.

Please seek advice by contacting NHS 111 or your GP if you experience any of the following:

- sudden worsening of breathlessness and, or wheezing

- sudden and persistent chest pain

- coughing up blood

Document control

- Document reference: DP8761/03.23.

- Date reviewed: February 2023.

Page last reviewed: July 19, 2024

Next review due: July 19, 2025

Problem with this page?

Please tell us about any problems you have found with this web page.

Report a problem